Real event OCD — also called real-life OCD — involves obsessive thoughts about events that have already happened. Here’s what it is and how to identify it.

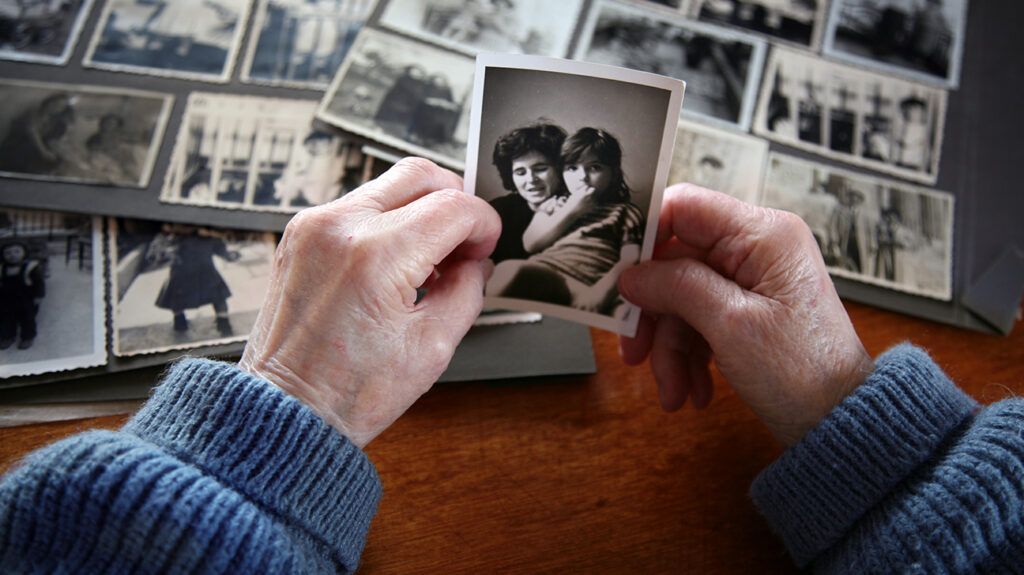

Many of us replay previous events in our heads, especially if they evoke feelings of regret or guilt. However, in some cases, replaying these events can be a symptom of OCD.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) involves persistent, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions). Every person with OCD experiences different obsessions and compulsions. Some people with OCD experience something called “real event OCD.”

Real event OCD is not a subtype of OCD, but a symptom of OCD. It involves having obsessive thoughts about an actual event that occurred and having compulsions related to those thoughts. The obsessions often focus on what you did or didn’t do in a specific situation.

People with OCD might experience real event symptoms as well as other symptoms of OCD.

For some people, OCD obsessions include things that haven’t happened — for example, you might have persistent anxiety about an accident or natural disaster that hasn’t actually occurred. In other words, it’s about a potential future situation.

Real event OCD is different because it involves obsessions about things that have already happened. You might replay the event over and over in your mind, seeking answers or imagining a better outcome.

As an article published on the Anxiety and Depression Association of America website notes, “real event OCD” is not a separate disorder from OCD. It is one of the many ways that anxiety shows up.

Typically, you’ll think about the event and analyze what happened. You might have persistent thoughts about what you did or didn’t do. People with real-life OCD might have obsessive thoughts along the lines of:

- Did I offend that person?

- Do my actions make me a bad person?

- Did I inadvertently cause a tragedy to occur?

- Should I have done something differently?

- What would’ve happened if I didn’t say or do that thing?

- Did I commit a crime or sin or do something morally reprehensible?

- What will happen as a result of my actions?

- Am I a good or bad person?

Although everybody worries about their actions from time to time, real-life OCD takes this to an extreme. Someone with real-life OCD might lose hours to these obsessions and compulsions. It’ll likely get in their way of functioning, and their relationships, academic or work performance, and daily tasks might be affected by it.

An example of real event OCD is that someone who drank a glass of wine while pregnant might have persistent thoughts that their child will have health issues as a consequence. As a result, they might seek reassurance from multiple doctors. However, this reassurance alone is unlikely to soothe those obsessive thoughts.

The symptoms of real event OCD include:

- replaying events repeatedly again in your head

- analyzing the outcome of your actions

- wondering whether you could’ve done something differently

- worrying about whether your actions make you a good or bad person

- seeking reassurance that you’re not a bad person

- apologizing excessively to those involved

- researching excessively to determine the possible outcomes of your actions

- feeling excessive guilt or doubt about your actions

However, because real event OCD is not a separate disorder from OCD, you can’t be diagnosed with real event OCD — it’s not a diagnosis in itself, just a term used to describe one way OCD can manifest.

To be diagnosed with OCD, a qualified professional needs to assess your symptoms of OCD and check whether they fit the criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).

The DSM-5 notes that signs of OCD may include:

- unwanted, upsetting, persistent thoughts or urges (obsessions)

- specific acts performed repeatedly to make these thoughts go away or soothe your upset (compulsions)

According to the DSM-5, in order for you to be diagnosed with OCD, your obsessions and compulsions must take up at least an hour of your day or affect your daily functioning.

It’s not clear what causes OCD and other anxiety disorders.

It seems that genetics can play a role in determining whether someone has OCD. Environmental factors and your personal temperament might also put you at risk of developing OCD.

Some research also suggests stressful and traumatic situations can trigger OCD, as can a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or a bacterial or viral infection.

Many people develop OCD for no clear reason.

Like all kinds of OCD, real event OCD is treatable. Although OCD cannot be “cured,”

Therapy

The most common treatment for OCD is a kind of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) called exposure and response prevention (ERP). Research has concluded that ERP is an effective way to treat OCD.

ERP involves managing obsessions without engaging in compulsions. Although this can be difficult at first, it eventually reduces the effect of the obsessions.

Other forms of therapy, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and psychodynamic therapy, may be used to treat OCD.

Medication

Certain medications might be helpful for people with OCD. This could include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are often used to treat depression and anxiety. These are prescription medications that are typically prescribed by a psychiatrist or general practitioner.

Self-care strategies for OCD will differ from person to person. It might be helpful to discuss potential strategies with your therapist.

Healthy lifestyle choices, such as eating a nutritious diet, getting enough sleep, and avoiding excessive caffeine and alcohol, might be helpful for you. These factors can all affect your overall mood and functioning.

Support groups might also be helpful. You can look at the IOCDF OCD support groups list for local meetup groups and the IOCDF online or telephone support groups list for remote support groups.

Relaxing activities, such as mindfulness meditation and exercise, might also help. You might also benefit from engaging in creative hobbies, which can be a great way to process and express your emotions.

You could also try an OCD workbook, such as “Getting Over OCD: A 10-Step Workbook for Taking Back Your Life” or “The Mindfulness Workbook for OCD.”

Lastly, real event OCD often entails regret, shame, and guilt about the way you acted in a specific situation. Whether you were truly wrong or not, try to respond to those thoughts with compassion. All humans make mistakes, but nobody deserves to obsess over those mistakes to the point of dysfunction.

For more information on OCD treatment, take a look at this article.

What does real event OCD look like? While it varies from person to person, the following example might help you understand and recognize real-life OCD.

Example

Situation: When you were a child, you said something cruel to a classmate. Decades later, you discover that they’ve been diagnosed with clinical depression.

Obsession: You might wonder if your words contributed to their depression. You might replay what you said repeatedly. Based on this, you might conclude that you’re a terrible person.

Compulsion: You might research clinical depression and seek reassurance from other childhood friends. You might apologize excessively to them and consider ways to “fix” the situation or make up for what you did.

Exposure: Speaking about what you read in therapy could act as exposure. The exposure will elicit the anxiety, and then your therapist will help you apply management techniques through this experience. Although avoiding compulsions can be very difficult, it might help you manage the obsessions better.

Real-life OCD, also called real event OCD, is one of the many ways OCD shows up.

Fortunately, as with all kinds of OCD, real-life OCD can be treated. Through talk therapy, self-care, and perhaps medication, it’s possible to manage real-life OCD in a healthy and effective way. A good way to start is by finding a therapist who is experienced in treating OCD.